Reflecting on 2025

This has been quite the year, hasn’t it? I started 2025 with a January trip to California, where my father lives, and when I look back at that trip now I feel as though I am peering at it through the wrong end of a telescope. Is that really me?

Reflecting on making

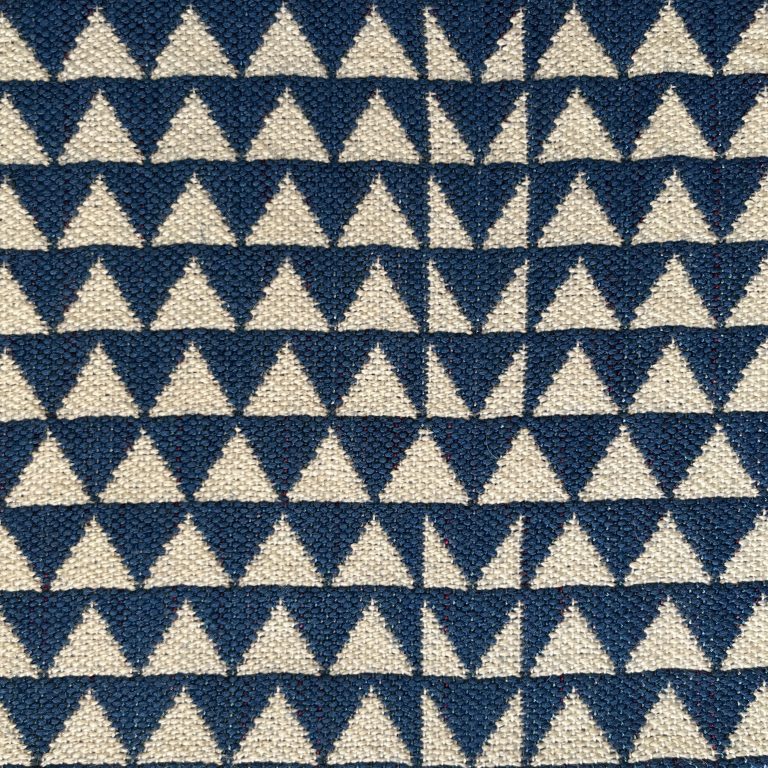

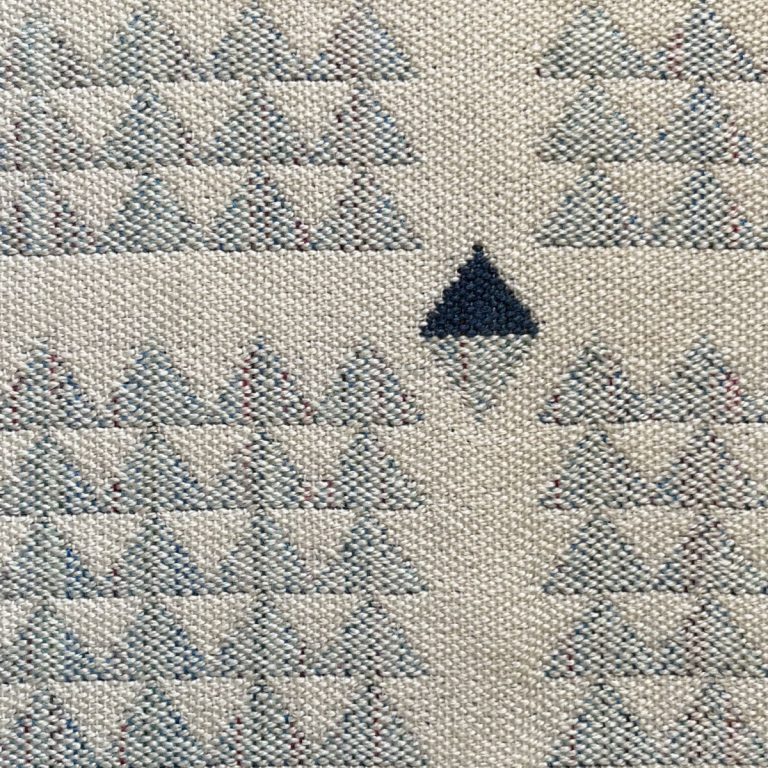

I’ve enjoyed every minute I have spent at the loom this year, but there simply haven’t been enough such minutes. Most of my scarce weaving time has been spent sampling, experimenting, exploring, which I absolutely love. So I am trying not to feel too disappointed that I don’t have any significant new work to show for it, because that will come. But it does sting a bit, no getting away from that.

The new work I have completed has been at the computer, where I have spent hundreds of hours over the last two years. Those hours have delivered one finished manuscript, over five hundred captioned images, four rounds of proofing and now, at last, one forthcoming book Designing and Weaving Double Cloth. It’s been intense! I am grateful to have got this far (there were many, many moments of doubt) and am looking forward to sharing more about it as publication day approaches.

There are two things about this experience which stand out for me. One is that I could not have done it alone, and I am immensely thankful for everyone who has helped me bring this project to its conclusion. That includes people who cheered me on, people who gave me feedback, people who lent me their skills, people who taught me new skills, and many more.

And that brings me to the other notable thing, which is that I have particularly enjoyed extending my skills in areas I had never previously thought about. Writing doesn’t scare me, but vector illustration certainly did! And now I am turning out diagrams and mocking up page layouts as if Adobe Illustrator were my second home. It’s never going to be my strongest suit, but it’s been a pleasant surprise to find that I am holding any cards at all.

Reflecting on changes

I’ve already blogged about the big move, so I don’t have much to add here. The possibility had been bubbling in the back of my mind for the last couple of years, but until I had submitted the book manuscript to the publisher, I didn’t have enough space in my head to turn the idea over and look at it from all sides. I must say that it feels seriously good to reach the end of this year with both of these giant tasks accomplished.

There’s an aspect of this year which I haven’t yet shared beyond family and friends, because it feels rather the wrong size and shape in the context of everything else in the world. But our feline companions have often featured in this blog over the years, so I think I should bring things up to date.

We started 2025 with three lovely cats: our senior cat, Polly (aged seventeen or eighteen), and ‘the kittens’, Pippi and Magnus (who actually turned nine last year). We end the year with none.

Pippi had a lymphoma and died in January. Polly was overtaken by old age and kidney failure and died in April. Magnus had very complex health issues, which he had been an absolute trooper about for over a year, but took a sudden downturn and died in August. We knew that these things were coming, but to have them come so thick and fast has been brutal. We miss them dreadfully.

Reflecting on inspiration

This year has been a peculiar one for inspiration. On the one hand, I have been so intensely absorbed in the things immediately in front of me – three sick cats and one demanding manuscript – that I feel I have hardly raised my head to look around me. On the other, the book project has brought me into places where I am spending a lot more time with writers than I have done before, and it’s been fascinating to get that glimpse of another creative process.

Here are a few things I’ve been reading, which could be loosely grouped under the theme of inspiration:

The energy I’ve met in writerly humans is positively buzzing, and in stark contrast to all the bland drivel being generated by AI, and I love that. I’ve always enjoyed words and reading – and remain defiantly human both in my self-expression and my use of dashes – but I am now very clear in my own mind that while writing is part of my work, writing is not my work.

Reflecting on teaching

One of the things that most reliably inspires me is teaching, because I love spending time with other weavers. And I learn so much!

In the first place, turning a topic into a workshop is a fantastic way to clarify my own thinking about it. It forces me to slow down, to articulate what I know, to unpick what I don’t know, to do more research and experimentation, to identify the underlying principles, to find analogies, to discover how to communicate it all. It’s such a rewarding process.

And then I get to surround myself with weavers, all bringing their own expertise into the class, and I learn even more, both from their weaving experience and from their response to the workshop. It’s learning all the way down! Honestly, I couldn’t ask for a better job. If you’ve been part of a workshop in 2025, know that weaving with you has been one of the highlights of my year.

So that’s 2025, or almost. As for 2026, I am going into it with the expectation of spending a great deal less time at the vet and the intention to spend a great deal more time at the loom. How about you?

Reflecting on 2025 was posted by Cally on 18 December 2025 at https://callybooker.co.uk